Fragmented Welfare: Human Interventions in Digitalised Food Assistance in England (Photo Series)

Authored by:

This photo series by Yasmin Houamed explores the everyday practices and improvised adaptations that arise as welfare and social support systems move increasingly online. In England, access to state welfare services – including food assistance – is now mediated through online registration forms, digital journals such as those used for receivers of Universal Credit, apps developed by businesses to distribute surplus food, and QR codes on electronic vouchers. Yet the lives of those who rely on these systems rarely match the frictionless digital future imagined by policymakers. Access to data for internet access and to devices, digital literacy and other poverty-related constraints all shape people’s ability to claim the support they are entitled to. In response, ad hoc infrastructures have emerged: charities, food banks and a wide range of volunteer-led intermediaries.

The photographs in this series were gathered during fieldwork in Northeast England (Gateshead, Hartlepool), Birmingham and London (Newham and Barnet) between November 2024 and May 2025 and illustrate the human work and material improvisations required to navigate digital welfare systems.

No digitalised welfare or food assistance practice was able to function without human support to enable access. This included developing complementary paper-based systems or alternative digital ones. The images of these practices expose the widening gap between the policy to digitalise welfare and food assistance and lived experience, revealing how communities themselves become the infrastructure that fills the void where the digital state does not yet reach. Pictured (with captions below) are the many intermediaries who have stepped up – mostly as unpaid volunteers – to provide support that the state should shoulder.

Photo descriptions:

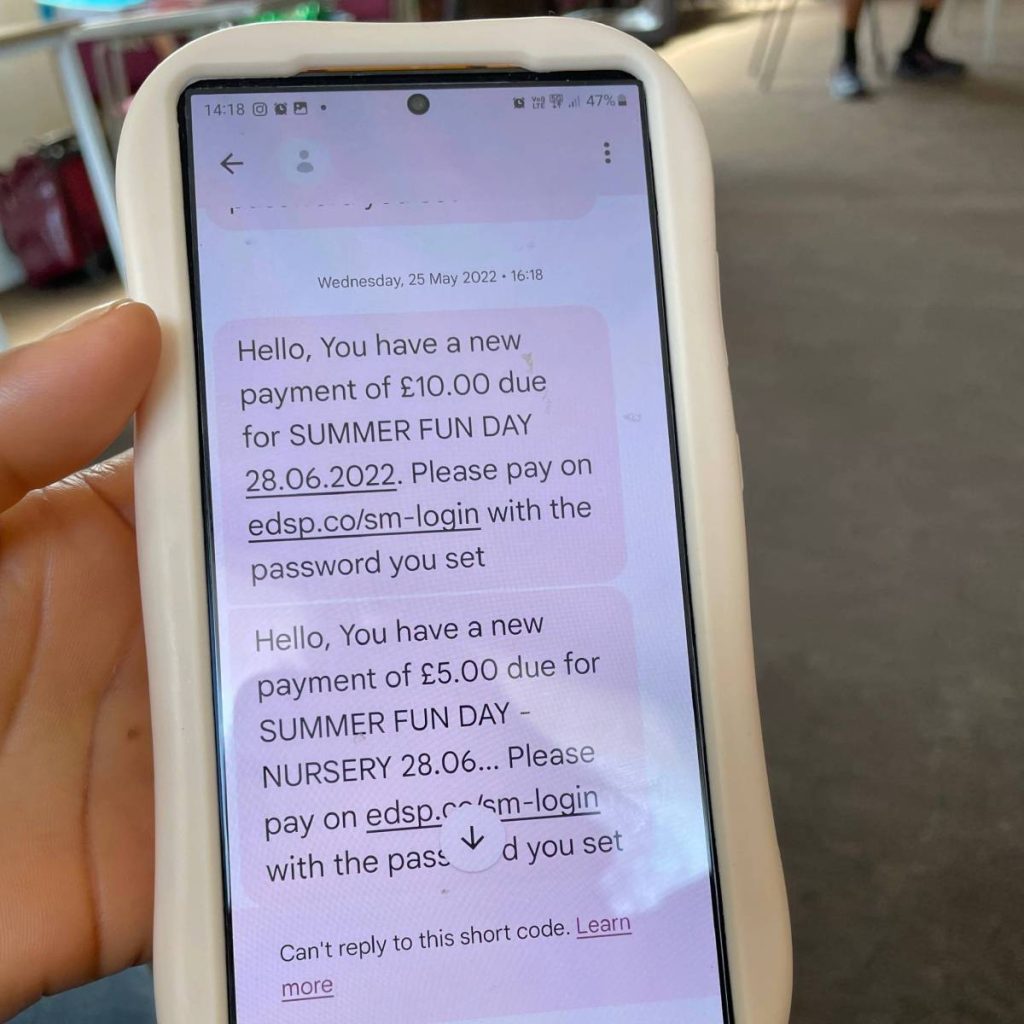

Top left

A mother at a Newham foodbank manages Holiday Activities Fund vouchers, which requires setting up an account with an email and password. The procedure is cumbersome on phones, and there is no direct support for navigating the digital system.

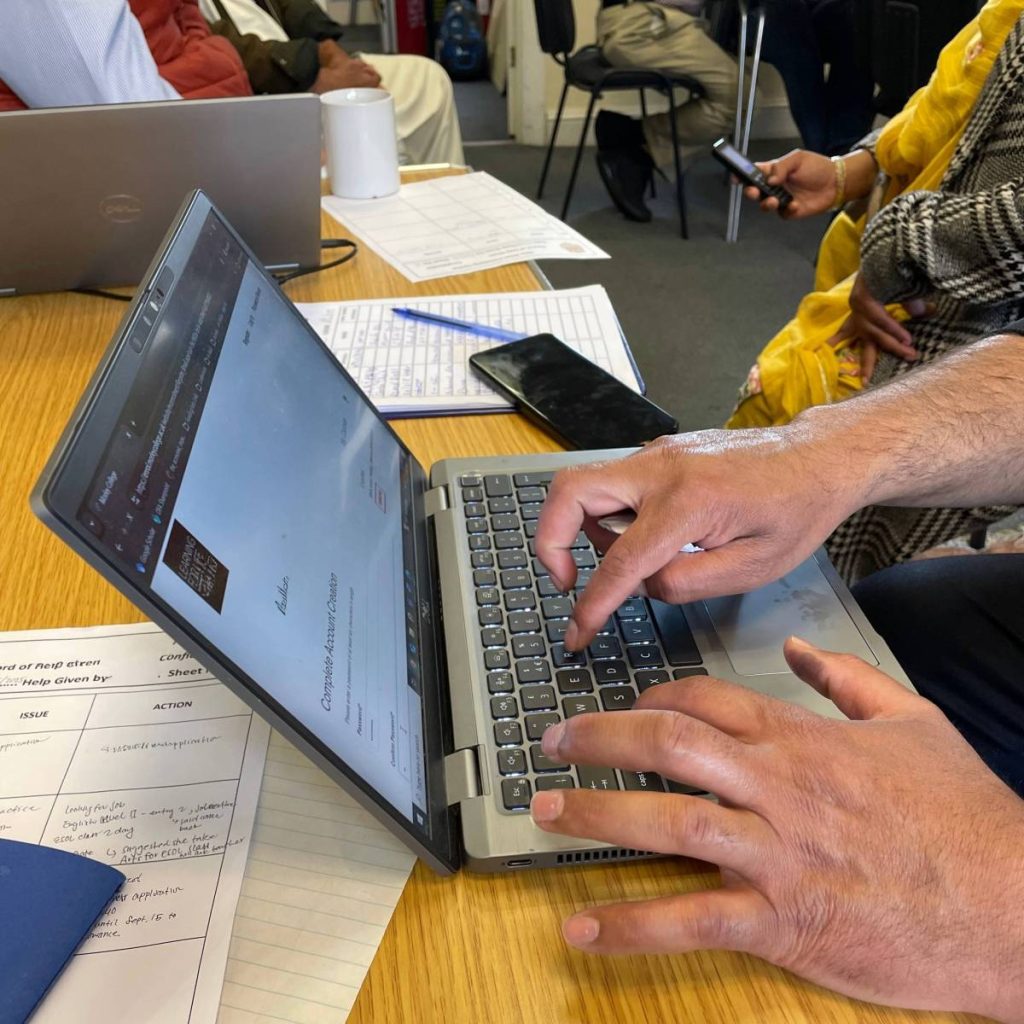

Top centre

In a Newham digital support hub, a volunteer helps someone register for digital literacy classes. Paper logs track each client’s progress – some requiring dozens of hours of support. People wait for help as volunteer capacity is stretched, and a mix of devices – from laptops to basic brick phones – reveals the uneven landscape of digital access.

Top right

A bakery in Birmingham encourages residents to donate food items for redistribution through a local foodbank, while its storefront displays a “Save Our Libraries” campaign. With library closures limiting access to computers, printers and benefits advice, food security and digital exclusion become intertwined issues.

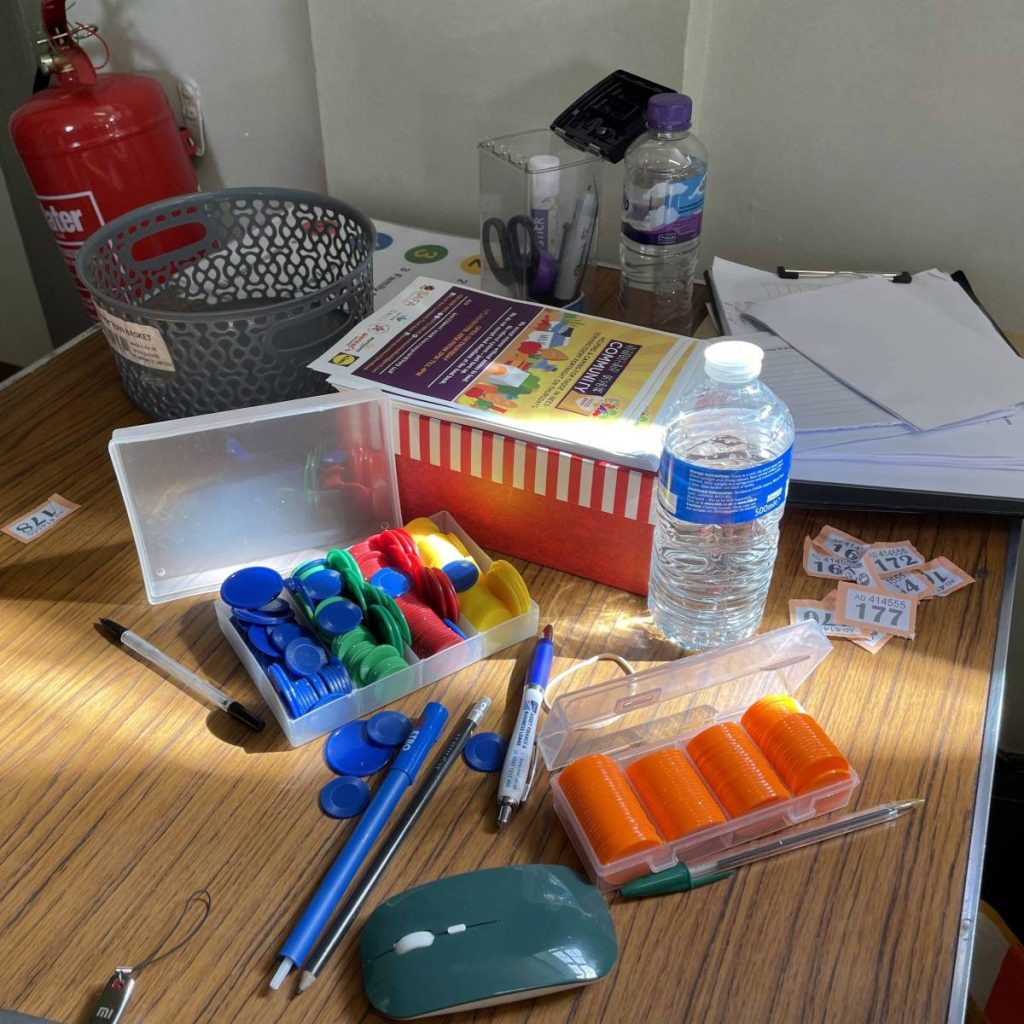

Middle left

A London foodbank has developed its own system to take stock of its users by using physical tokens instead of the council’s digital data-collection platform. Colour-coded tiles denote user categories, enabling volunteers to allocate food by keeping track of who uses the food bank as well as how many, without relying on a complex digital system that they lack the capacity to implement or maintain.

Middle centre

In Birmingham, a Nigerian couple with young children who avoid foodbanks due to stigma rely on an online community network that shares alerts about religiously appropriate halal food deliveries. Digital platforms can become a discreet work-around for accessing support without entering formal systems.

Middle right

A digital inclusion course in Birmingham focuses on building older adults’ confidence online – teaching them to use apps for creative play (such as digital drawing) and note-taking – yet instructors are unable to support participants with online welfare applications or financial tasks (for example online banking) that require specialist guidance and carry data privacy risks.

Bottom left

In rural Gateshead, a café hosts a community fridge and freezer designed to feel welcoming and non-stigmatising. Many local residents are food insecure, have low literacy and are reluctant to engage with formal benefits systems, making this analogue, open-access model an important alternative.

Bottom centre

Just around the corner, a local grocery store struggles to maintain fresh produce. Combined with low digital literacy, the scarcity of nearby food stores makes surplus distribution apps largely irrelevant, highlighting how rural food insecurity emerges at the intersection of physical and digital exclusion

Bottom right

Many foodbanks in England now use digital apps to collect unsold supermarket food, but these systems bring multiple challenges: collection windows clash with volunteer schedules, pickups are physically demanding, food quality varies, and app glitches are frequent. Managers stressed that building relationships with supermarket staff remains the most effective way to secure surplus. Apps for individual pickups face similar problems, including payment requirements and narrow collection windows.

Photo credits: Iris Lim, Susanne Jaspars and Yasmin Houamed